On 24 January 2024, a GFMD civil society side event highlighted the challenges faced by families of missing migrants, and drew on experiences in Latin America to make recommendations on strategies for solutions.

On the second day of the 14th Summit of the 2023-24 Global Forum on Migration and Development (GFMD)* under the French Chairmanship, held in Geneva on 23-25 January 2024, Latin American civil society representatives came together to host ‘Advances in the Identification and Search for Missing Migrant Persons,’ a GFMD side event highlighting the issue of missing and disappeared migrants.

Co-organised by Red Regional De Organizaciones Civiles Para Las Migraciones (RRCOM) and Bloque Latinoamericano Sobre Migración (Bloque LAC), the 2-hour side event focused on identifying challenges, opportunities, and joint recommendations for progress on search and investigation strategies for missing migrants.

“For us, it was so important to bring this issue to the GFMD, because in our discussions on migration we seem to have lost the perspective that people die or disappear while they are migrating,” explains Helena Olea of Alianza Americas and RRCOM. “That conversation is absent from our migration discussions, and it absolutely needs to start.”

Referring to work being undertaken in support of Objective 8 of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM),** which calls on State signatories to implement measures to ‘save lives and establish coordinated international efforts on missing migrants’, Olea also highlighted the side event’s aim of creating greater dialogue and complementarity between the GFMD and GCM processes in this regard.

‘We are many, and we need to know the truth’: families of missing migrants

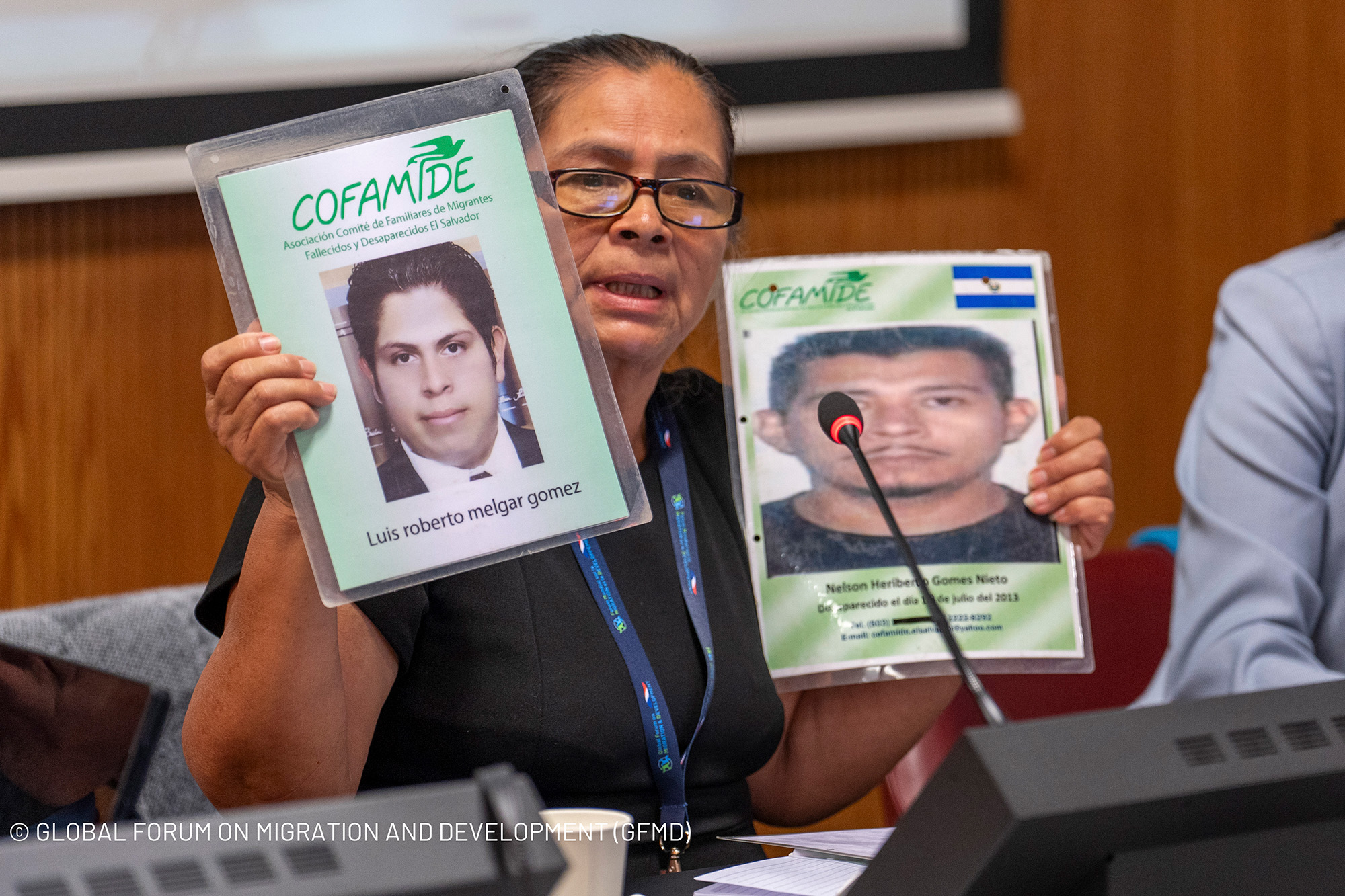

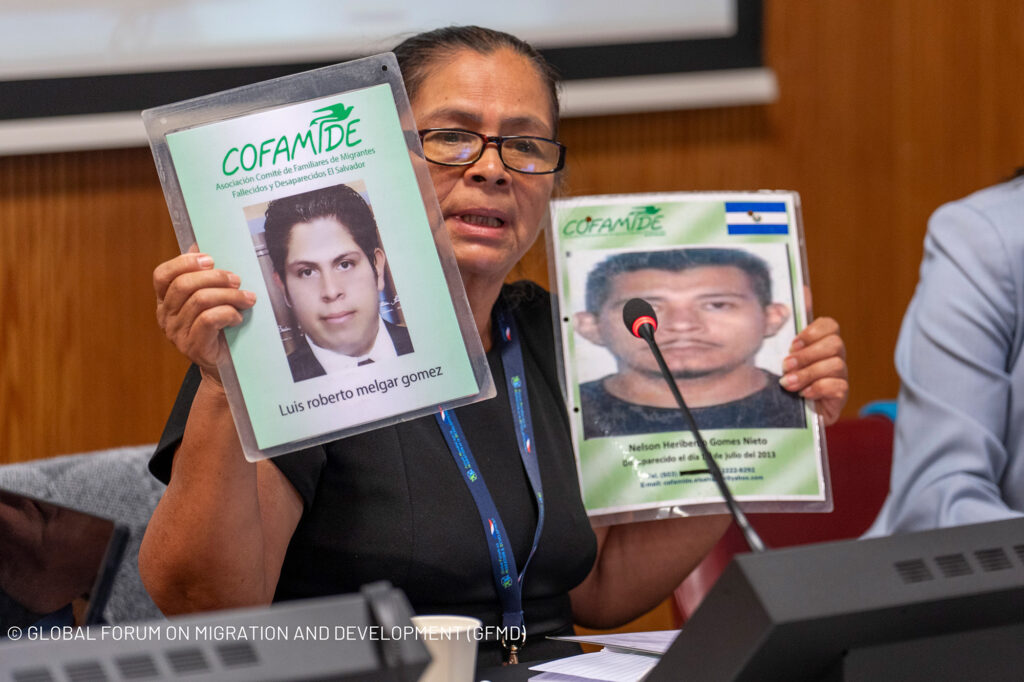

The experiences and realities of the families of missing migrants were brought directly to the GFMD via a powerful intervention at the side event by Blanca Gómez, a member of the Comité de Familiares de Migrantes Fallecidos y Desaparecidos de El Salvador (COFAMIDE) who has been searching for her son and her brother for many years.

“My youngest son left El Salvador for the U.S. more than 13 years ago, and my brother a decade ago, but for me it’s like it was yesterday,” she stated. “It’s what we live, day and night – we’re not complete until we know what happened to our children.”

“My youngest son left El Salvador for the U.S. more than 13 years ago, and my brother a decade ago, but for me it’s like it was yesterday,” she stated. “It’s what we live, day and night – we’re not complete until we know what happened to our children,”

Blanca Gómez, member of the Comité de Familiares de Migrantes Fallecidos y Desaparecidos de El Salvador (COFAMIDE)

Gómez highlighted the lack of state assistance for families searching for missing relatives, and the long-term impact this has on their lives. “We stay where we are so they can find us, but there should be a government register to take care of this – we families can’t do it,” she explained. “I see a lot of interest, lots of papers and research, but there is little to no assistance for families searching on the ground. Governments are supposed to protect people, but they don’t and they didn’t, and no one pays.”

Olea notes the challenges of bringing together the diverse and multiple organisations established by families of the disappeared to search for their relatives in the absence of coordinated state support. “Organisations are often structured around a particular missing person, a specific incident, the fact that a group of relatives come from the same part of a country, or that they met during the search for their loved ones,” she explains. “That is how organisations form, but it does present an obstacle to organising, and to creating a strong collective voice for families within advocacy and dialogue.”

Despite these challenges, collective grassroots organising by families has created visibility for the issue of missing migrants, although not without personal cost. Gómez is part of the Caravana de Madres de Personas Migrantes Desaparecidas (Caravan of the Mothers of Missing Migrants), which has travelled across Mexico every year since 2005 searching for disappeared loved ones and demanding policy change. “We are old now, I’m sixty, and it’s very hard,” she says. “But we have to do it because it’s the only way to raise awareness and demonstrate our pain.”

Bringing testimony, sharing practice: Engaging States in the issue of missing migrants

“Blanca’s testimony showed just how crucial it is for the organisations of the relatives of the disappeared to have the support of their governments,” says Olea.

She highlights the specific role of consular officials in facilitating visits to prisons and jails, and of governments more broadly in supporting relatives in their advocacy. “Another critical aspect with which governments can help is the exchange of DNA data, but this is a very new area, where things are currently done largely by non-profits and on a case-by-case basis,” she continues. “It needs to be systematic, with established protocols, ideally via state-sponsored programmes where data is gathered in one place by governments.”

The GFMD side event included an intervention by Ambassador Yessenia Lozano of El Salvador. Olea considers systematically engaging states in discussions in this way as crucial in building their commitment to act. “It was so important to have an Ambassador sitting next to Blanca at a side event saying, ‘I was moved by this, throughout my career I’ve heard about this, I know this happens, and we have to do something’,” she reflects. “In the future she might be in another critical space where this issue comes up, and she will be ready to advocate for action.”

The UN Working Group on Forced Disappearances, established by the Human Rights Council, provides a mechanism to prompt and support State action. It communicates with governments regarding individual cases, and requests that States investigate and inform the Working Group of the results. Acting as an interlocutor between States and families of the disappeared provides a platform to establish dialogues with States on forced disappearances. The Working Group also conducts country visits, receives complaints, and provides annual reports on its work to the Human Rights Council.

At the side event, the Working Group’s Professor Ana Lorena Delgadillo introduced their work on forced disappearances in the context of migration. She emphasised the key findings of the Report of the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, which concludes that there is a direct link between migration and enforced disappearance, but that States and the international community are not paying the necessary attention to this issue in terms of either policymaking or international cooperation.

“We don’t have clear data on disappearing migrants, and countries of origin, transit and destination have a responsibility to collect this, even though it’s challenging,” she remarked. “Countries of origin in particular have a responsibility to protect their citizens overseas, and current inaction by States means that families need to go to prisons or retrieve remains themselves. This is unacceptable.”

Delgadillo highlighted instances of good practice gleaned from the Working Group’s country visits, such as that of an African organisation documenting migrant departures and arrivals, and the role that technology can play in facilitating these types of approaches. “It’s really important to share both best practices and practices that don’t work,” she said. “There are a lot of examples at the national and regional levels that could support States, but they are not being adequately shared at present.”

One such example was presented by Eduardo Canales of South Texas Human Rights, a community-based organisation that seeks to prevent migrant deaths at the Texas-Mexico border and strengthen the capacity of families to locate their missing loved ones. “We work with families to locate their missing relatives using GPS coordinates provided by mobile phones,” he explained. “We also maintain lifesaving measures such as water stations, and work to ensure that the state of Texas fulfils its obligations to collect DNA samples for all remains, including those of migrants.”

Canales described the partnership work on identification taking place via the Forensic Border Coalition, which collects DNA samples from families to match to remains. “Our goal is that no remains are unidentified, and that the state’s DNA database is fully employed for this purpose in relation to migrants. We’ve identified more than 100 people in our county during the past year, but we also know that many more are not being found. That’s just one county, so the numbers are huge.”

Clear responsibilities, limited action: international legal frameworks for forced disappearance

Recent international law provides a useful framework for further engaging states. The International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (ICPPED), which came into force on 23 December 2010, has to date been signed by 99 States and ratified/acceded to by a further 13.

An intervention by Barbara Lochbihler, an independent expert member of the UN Committee on Enforced Disappearances (CED) created by the Convention, presented States’ obligations in relation to action on enforced disappearances according to the Convention. “We know that thousands of people are missing, and that many may be victims in the sense of the Convention,” said Lochbihler. “State parties have obligations to act, both in relation to prevention and when a disappearance has occurred.”

In September 2023, the CED issued a setting out State parties’ obligations in these two areas. “General Recommendations are soft law recommendations by UN treaty bodies, but they can influence both national jurisprudence and international and human rights law,” Lochbihler explained. “We also hope that our recommendation can be an advocacy tool for civil society, and a resource for international organisations to include forced disappearances of migrants within their work.”

Despite the obligations of State parties to the Convention, meaningful action remains limited. Speaking at the side event, Claudia Interiano of Fundación para la Justicia highlighted the example of Mexico, which has ratified the Convention but where action remains limited.

“There is a broader context of forced disappearances in Mexico, where rights violations at borders and mass disappearances have been going on for years,” she stated. “In Mexico, we need a national commission and true cooperation between the state, civil society and families, but we also need transnational cooperation, which is so important in this context.” She urged Mexico to better engage transit countries by pursuing bilateral agreements. “We should be looking to existing mechanisms in which the issue of forced disappearances can be made prominent, and around which this cooperation can be structured.”

Olea points to the need for political commitments to make legal frameworks meaningful. “The Convention is, of course, positive, but the challenge is which states are party to it and which aren’t,” reflects Olea. “And then it’s about enforcement, which has its limits. We need political will.”

Looking to the future: next steps for advocacy and action on missing migrants

At the side event, Delgadillo called on States to change the context for migration by introducing secure and rights-based migration pathways that reduce the precarity of migrant journeys. “Forced disappearances in the context of migration often occur in contexts of rights violations and violence at borders, including via pushbacks,” she remarked. “These are worldwide issues that we need to investigate, but the key policy change is to make migrants and migration safer.”

For Olea, it is clear that there is much more work to do. “We are here at the GFMD in Europe, and although we should be talking about the Mediterranean in this context, there is silence,” she says. “We have been reflecting on the very scarce participation of European civil society in this issue so far. They maybe feel it’s more effective for them to invest in other spaces, such as advocacy within European Union structures, rather than coming to this space.”

The specific history of forced disappearances in Latin America may provide an answer. “Forced disappearances started to be named as such in the Southern Cone of Latin America under the various dictatorships and in the context of forced disappearances by the military,” says Olea. “So there is a trajectory and a legacy around this topic in Latin America, and in the context of migration this sadly continues to be a crime that is perpetrated by state actors and criminal organisations.”

She hopes that advocacy in spaces such as the GFMD will boost the profile of the issue of missing migrants at the international level, and support advocacy and action at other levels. “We will continue our advocacy at the domestic level, and use the Cartagena +40*** process and the regional review of the GCM as valuable spaces,” she concludes. “At the global level, we particularly hope for further engagement of European civil society. This is not just an issue for Latin America, and we must work together to ensure that families all over the world receive justice.”

***

* The Global Forum on Migration and Development (GFMD) is a government-led initiative that brings together member states, local government, business representatives, and civil society organizations concerned with migration and development issues. Its goal is to discuss a range of topics on migration, propose innovative solutions, share policy ideas, and create partnerships and cooperation in an informal dialogue setting. ICMC has coordinated civil society engagement in the GFMD since 2011.

** The Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration is an international agreement adopted by 152 States in December 2018. As the first-ever global framework for migration governance, it aims to increase international collaboration on all aspects related to migration, including human rights, humanitarian needs, and development.

*** 2024 marks the 40th anniversary of the Declaration of Cartagena. On the occasion, countries of the region have launched consultations dubbed the Cartagena +40 Process, which will produce a new 10-year strategy for protecting refugees, displaced, and stateless people.